We Need to Talk About Our Ecological Grief

There’s a feeling I’ve come to expect when I see pictures and videos of natural disasters.

Whether it's a wildfire, hurricane, flood—the feeling is always the same.

You might know it: It starts like a sucker punch in the pit of my stomach and creeps up to my chest, making it feel tight and tense. Then, it settles on my shoulders like a heavy weight.

It turns out, there’s a term that more and more people are using to speak to this feeling: ecological grief.

“Ecological grief is the pain, sadness, and feelings of loss that we experience when we witness or we lose an environmental place or species or body of water,” researcher Ashlee Cunsolo, Ph.D., director of the Labrador Institute of Memorial University in Labrador, Canada, tells Shine. “It’s the grief that we feel beyond humans.”

'Ecological grief is the pain, sadness, and feelings of loss that we experience when we witness or we lose an environmental place or species or body of water.'- Ashlee Cunsolo, Ph.D.

Cunsolo has spent the past twelve years studying the impacts of climate change on mental health, and she first learned about the term “ecological grief” when conducting interviews with Inuit communities in Labrador. In this region, climate change has impacted the ability to travel on the land and ice, threatening the traditional Inuit lifestyle. “Inuit are people of the sea ice,” she heard in one interview. “If there is no more sea ice, how can we be people of the sea ice?”

“That’s when I learned about the term ecological grief—it really came from the Inuit I was working with and how they described it as grief related,” she says. “And it resonated with me. They were giving voice and definition to what myself and many people are feeling in the changing climate.”

When I first learned the term, the Australian wildfires were in full force—as was the anxiety and sadness I felt.

The term resonated with me deeply, and the more I shared it with friends and family and co-workers, the more I realized we were all experiencing a level of ecological grief as we witnessed what was happening on the other side of the world.

According to Cunsolo, it’s a natural human response.

“As humans, we are part of the ecosystems that we live in and within the animal kingdom, so there’s this innate connection to the environment whether we realize it or not,” Cunsolo says. “The extension to mourning beyond humans is a normal response to climate change.”

'The extension to mourning beyond humans is a normal response to climate change.'- Ashlee Cunsolo, Ph.D.

While others have advocated for a term like “ecological hope” instead of “ecological grief,” Cunsolo says calling the feeling what it is—grief—is one of the most important things we can do.

Why: It validates the difficult experience so many people across the world are having. Plus: She believes there’s power in collective grief.

“If we look at grief as a political mechanism and not something to be terrified of or shy away from but something to talk about and use to come together, that’s where there’s an incredible power in grief,” she says.

If you’re experiencing ecological grief like I am, here’s how to cope with the feeling and use it as a catalyst for action.

1. Know It’s Healthy to Have Ecological Grief

We’re wired to want to fight negative emotions when they appear, but ecological grief is a natural response to ecological loss. In fact, Cunsolo says if we suppressed that response, it’d be doing ourselves a disservice. “The good health response is that we’re mourning,” she says.

As difficult as it may feel, see your ecological grief as a sign that you value the natural world around you and the people impacted by its changes. Accept that it’s a sign that you care.

Also: Know you’re not alone in feeling worried or sad.

A 2019 survey by Yale and George Mason University showed that two in three Americans are “somewhat worried” about global warming—with 30% being “very worried.” Google searches for “eco anxiety” and “climate change anxiety” have also spiked, reaching all-time highs in 2019.

Courtney Howard, M.D., an emergency physician and board president of the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment, told WNYC that part of her work in talking about ecological grief is helping people feel less alone.

“When I give presentations, I still often have people coming up to me at the end of a presentation with tears in their eyes saying, ‘I thought I was the only person who was this worried about climate change. Now I know I’m not the only one,’” she said. “It makes people realize that it’s normal to be worried about this change in our planet and what it means for our health and our kids' health.”

2. Start Talking About Your Ecological Grief

Ecological grief is seen as a form of “disenfranchised grief,” meaning it isn’t often publicly or openly acknowledged. A 2019 survey showed that 59% of Americans said they “rarely” or “never” even discuss global warming with family and friends.

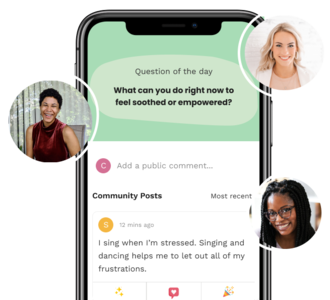

But opening up about ecological grief is one of the best things you can do—whether that’s talking with family, friends, an online or IRL support group, or a mental health professional.

Climate anxiety support groups have begun to pop up across the U.S. and abroad, and websites like Isthishowyoufeel.com are specifically designed to help climate change researchers process how they’re feeling.

“Being isolated with these feelings is the worst,” Howard told WNYC. “It’s a second type of suffering that we don’t need to have.”

'Being isolated with these feelings is the worst. It's a second type of suffering that we don't need to have.' - Courtney Howard, M.D.

One thing that can help you communicate how you feel: Knowing the type of ecological grief you’re feeling.

Cunsolo breaks ecological grief down into four types:

●︎ Acute: This stems from directly experiencing ecological loss, like wildfires, floods, and hurricanes. “This has a strong immediate mental health response and often very long-term mental health responses for many people,” Cunsolo says.

●︎ Cumulative: This is grief that builds from the daily stress, anxiety, and fear as the landscape around you changes—like when the Inuit communities slowly saw a change in their ability to travel across the ice for hunting and fishing.

●︎ Vicarious: This form of grief comes from seeing others suffer at the hands of ecological loss. It's a type of grief that social media and the news can trigger. “I think the Australian wildfires have become a global wakeup call for how deeply our mental health is affected by the suffering of others,” Cunsolo says. “And ‘others’ isn’t just people but millions of animals dying and complete ecosystems being wiped out.”

●︎ Anticipatory: Finally, this type of grief comes from the anxiety and fear over anticipated future losses. It’s thoughts like “Will this happen again?” and “Is this going to get worse?”—and these anxious thoughts can also seriously impact your mental health.

The next time you’re talking about an ecological loss with friends or family, try starting an honest conversation about how it’s making you feel. What you’ll likely find: You’re not alone in grieving.

And if your ecological grief feels especially overwhelming, know it’s OK to seek out a mental health professional. While ecological grief is not yet recognized as an official mental disorder, Cunsolo says mental health professionals are starting to incorporate more knowledge of it into their practices.

3. Greet Anxiety With Action

A key coping mechanism for ecological grief is greeting your anxiety with action.

“Talking about (ecological grief) does start to make people feel better immediately, and when we start to create solutions together, the psychological literature that’s emerging shows we start to feel better about it,” Howard told WNYC. “So action feels better than anxiety.”

It’s something Cunsolo says she’s seen youth climate activists—like Greta Thunberg—embrace early on, as they openly talk about their grief, anxiety, and fear around climate change as a main reason why they’re joining together and taking action.

“That’s when we’re starting to harness the power of these emotions,” Cunsolo says. “When we can really say, ‘I feel this way and so do others,’ we’re going to come together and push for a different world.”

What action can look like for you: Getting involved in climate marches, starting a sustainability “Green Team” in your workplace, adopting a more eco-friendly diet, divesting from fossil fuels, or simply finding small ways to change your daily habits to make them more sustainable.

Your impact might feel small, but research shows that it can kick off a ripple effect and encourage others to join in.

4. Spend Time in Nature

“There are so many different ways we know scientifically, spiritually, emotionally, and physically that spending time in nature has impacts on all parts of mental health,” Cunsolo says.

When you can, prioritize spending time outdoors and savoring the natural world around you. Look for moments of awe—whether it’s a beautiful plant, body of water, or peaceful green space. Enjoy the things you know are worth protecting.

It’s a tactic Cunsolo turned to when she felt especially traumatized by the news about the Australian wildfires. She went for a walk in the forest and reminded herself along the way, “You’re a forest. You’re not burned. This is a place where animals live.”

5. Set Boundaries When You Need Them

Finally, it’s important to monitor your levels of ecological grief and anxiety when a natural disaster is in the news.

For Cunsolo, that meant flagging when her obsession with the Australian wildfires started to spiral. “I found myself getting more and more sad and depressed,” she says. That was her cue to put down social media, turn off the news, and take a walk in the forest.

If you notice you’re dreaming about ecological loss or can’t stop thinking about it, know it’s OK to set a boundary to make sure you’re informed but not overwhelmed.

“Vicarious trauma really is real,” Cunsolo says. “We are witnessing people and places being burned and being destroyed and we can all empathize—these are important responses and not something we should be embarrassed of or ashamed of.”

For me, having the term “ecological grief” definitely made me more accepting of my feelings. It felt good to have vocabulary beyond “I can’t believe this is happening”—and it helped me shift from feeling helpless to actually talking with my friends about how we can all live more sustainably.

What I’ve come to realize: I can’t change how I feel when ecological losses occur—but I can change what I choose to do with the feeling.

What I’ve come to realize: I can’t change how I feel when ecological losses occur—but I can change what I choose to do with the feeling.

I can see it as a sign that I’m upset. That I feel helpless. That I feel overwhelmed.

But most importantly: I can see it as a sign that I care—and I care enough to do something about it.

Ecological grief will only start to impact more people as ecological losses continue. Our challenge now: To figure out the best way to cope, be open with one another, and use our collective grief not as a blocker but a catalyst for the change we wish to see.

It’s up to us to take care of ourselves together while we protect the world around us.

If you’re struggling with your mental health, know that seeking help is a strength—not a weakness. If you or someone you care about needs help, text 741741 to talk with a crisis counselor at Crisis Text Line—it's free, confidential, and available at all hours.

Read next: Your Complete Guide to Mental Health Days

Shine is supported by members like you. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. See our affiliate disclosure for more info.