The Case For Embracing The Career You Didn't Plan To Have

This piece originally appeared on The Well, Jopwell's editorial hub.

Four years into my career, I still feel somewhat awkward when someone calls me "professor." Why? Well, because I never imagined being here. By most accounts, I am not your everyday college professor. I did not spend years in a relentless pursuit of my position. Quite the opposite, in fact: I consider myself to be the accidental academic.

It sounds bizarre, but like so many young, Black males, in the 90s and now, I grew up with the misconception that playing professional sports was the only way to "succeed." By the time I arrived at Rutgers University with a full ride to play Division 1 football, I had already picked out my three-piece suit for the NFL draft. A little premature, I know.

I regret to say that I chose not to engage academically. Instead, I committed an array of academic improprieties, mentally crippling myself without even knowing it. Case and point: I didn’t read my first book in college, cover-to-cover, until my senior year. It was around that time that I realized the prospects of becoming a professional athlete were slim to none. A defensive back with a bum knee and little playing time under my belt, I just wasn’t good enough.

Forced to do something different, I started a personal renaissance of sorts. And as Audre Lorde powerfully wrote,

"If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive."

The problem was, I didn’t know who I was without sport. What was I good at? What and who did I want to be? How was I going to get there?

Because I didn’t know what do, my twenties became my blank canvas to try the different colors of life. I entered a master’s program, sold copy machines door to door in Los Angeles, was a doorman for the BET Awards After Party twice (I successfully avoided an unfavorable encounter with Suge Knight), worked in politics, acted in a later-cut scene of a music video, took the LSAT, tried modeling (with no success), interned for Congress, judged a beauty pageant, took the police exam for the LAPD and scored 98 percent, played neighborhood barber, and finally, gained admission into a doctoral program. Needless to say, these years were a bit all over the place.

But you still might be wondering, how did I become a professor? Well, my desire to jump into anything and everything naturally calmed down over time, and I discovered that the life of a doctoral student doesn’t lend itself to very much outside of reading and writing. By the time I began writing my dissertation on the academic exploitation of the student-athlete, I was determined to become an athletic director and stop the exploitation of Black male student-athletes, similar to what I experienced.

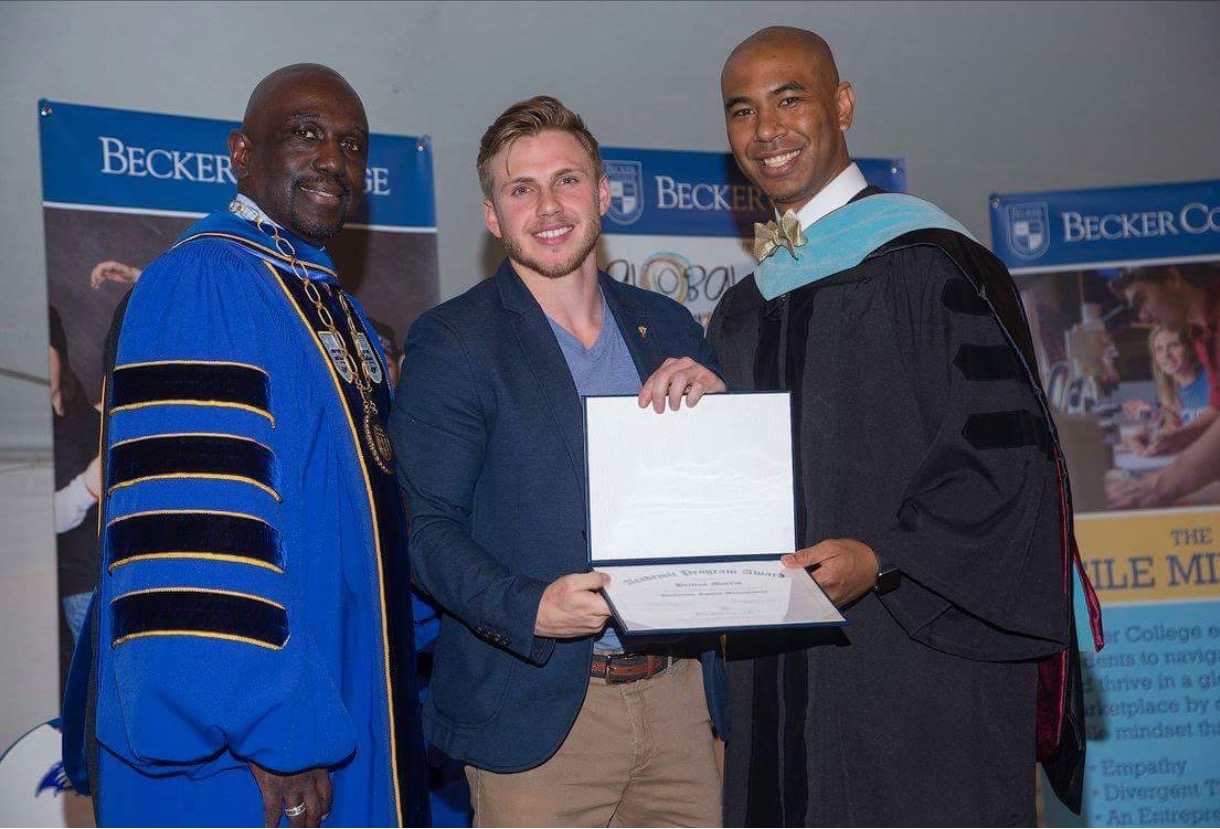

However, my dissertation advisor suggested that I give teaching a try, just about walking me into a class to guest lecture. I was kind of nervous. Okay, very nervous, but I got over it and spoke. Then, I did it again and again at other institutions. Before I knew it, I was interviewing to be a full-time assistant professor at a small liberal arts college outside of Boston. It’s now been four years since I started teaching, and I love it. So much that I think I just may stick with this for a bit, and leave my days as a salesman, doorman, model, music video actor, beauty pageant judge, and barber behind.

I hope that for others who are equally unsure about their paths, mine serves as a reminder of three things:

1. Embrace the road less traveled.

Of course, there are suggested pathways to a career, but there is no one way. Our paths are just that: ours. They are a hodgepodge of trial and error, good advice, not so good advice, encounters with interesting people, unwavering hopes, crushing reality, and hopefully a little bit of fun.

Never compare your path with someone else’s, because once you dig past the surface level, you’ll discover no two are identical.

2. Bet on yourself.

The notion of success is subjective, so there’s no reason to be crunched into other people’s definition of it. To find yourself and your success, you have to put yourself in a position for self-exploration. In other words, don’t be afraid to try something new because you are afraid.

When I was offered admission into my doctoral program, I had a choice: Stay in my comfortable $65K a year job, or give up the money and bet on my future self. Many people, including my family, told me I was taking too huge of a risk, but I could not and would not listen. I took a cue from William Ernest Henley and decided that I was the master of my fate and captain of my soul.

3. Establish a board of advisors.

In my late twenties, I realized that I had been playing the game of life without a coach or trusted mentor. I was operating under the the false impression that I could figure everything out myself. Sure, I was able to do okay, but I wanted to do better. That’s when my fraternity brother told me that, just as companies have boards of advisors, so should individuals.

Boards are there to advise, vet, redirect, listen, and support the growth of company. If Fortune 500 companies are willing to seek sage advice, we should probably consider doing the same.

As they say, there is no time like the present to create your future.

The Well is the editorial hub of Jopwell, the diversity recruitment platform that connects Black, Latino/Hispanic, and Native American professionals and students with leading jobs and internships.

Shine is supported by members like you. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. See our affiliate disclosure for more info.